What Michigan politicians need to learn about the Internet

In a tight election, politicians should express interest in fixing problems with Internet access and in promoting competition that results in competitive pricing as a replacement for territorial monopolies. This might make the difference in who wins and who loses.

This is the first of a series of posts that we intend to publish about the political platforms of the parties in multiple states within the USA. Millions of dollars are being spent on mapping whether or not particular populations have broadband Internet access and on defining those groups as unserved or underserved. Currently, “underserved” (see glossary below) is defined by the speed of Internet uploads and downloads from the home. Here, we argue that the definition for underserved should also include those households where only one provider is available. In those locations, a de facto monopoly exists and consumers have no choice. We have talked about Open Access in other posts, and how that enables a free market. Perhaps, Democrats, who are often accused of being socialists, should begin talking about a free market. And Republicans, who truly believe in a free market, should support Open Access.

We posed this question to our AI chatbot

Here is the question and answer:

User:

How does a politicians stance on digital equity and Internet access affect the voting behavior of their constituents in choosing a democrat or a republican?

AI:

The stance of a politician on digital equity and internet access can indeed play a role in influencing the voting behavior of constituents. In today’s increasingly digital world, access to reliable and affordable internet is no longer just a luxury but a necessity for education, employment, healthcare, and civic participation. As such, voters are becoming more aware of the importance of digital equity issues and are looking to support candidates who prioritize this issue.

When a politician takes a strong stance on digital equity and internet access, it demonstrates their understanding of the challenges faced by communities without reliable connectivity. They may advocate for policies that promote broadband infrastructure development, affordability, and digital inclusion initiatives. Such a stance can resonate with voters, particularly those who have experienced firsthand the disparities in internet access and the impact it has on their lives.

The effect on voting behavior can vary depending on the specific constituency. In areas where there is a significant digital divide and inadequate internet access, voters may be more likely to support a politician who emphasizes the need for bridging this gap. This could cut across party lines, as constituents from both Democratic and Republican backgrounds may recognize the importance of addressing digital equity. Furthermore, in today’s political landscape, technology-related issues are increasingly bipartisan in nature. Both Democrats and Republicans understand the significance of broadband access for economic growth, education, and overall societal well-being. As a result, a politician’s stance on digital equity may not solely determine whether constituents vote for a Democrat or a Republican. Other factors such as the candidate’s overall platform, their track record, and their alignment with the voter’s broader political values will also play a significant role in the decision-making process.

In summary, a politician’s stance on digital equity and internet access can influence the voting behavior of constituents, particularly in areas with significant connectivity challenges. However, it is important to consider that voting decisions are complex and influenced by a range of factors beyond a single issue.

Michigan stats

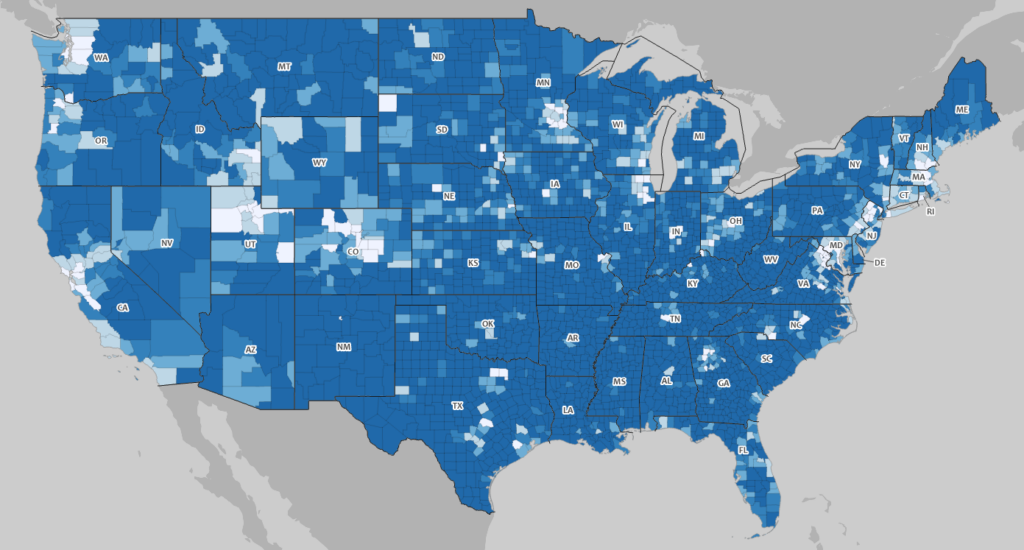

See the Digital Equity Act Population Viewer with data from the US Census Bureau.

- Total population: 9,986,857

- Total covered population: 8,051,000

- Covered population: 80.6%

- – In covered households: 20.9%

- – Aged 60 or over: 24.7%

- – Incarcerated: 0.6%

- – Veteran: 5.2%

- – With a disability: 14.7%

- – With a language barrier: 15.1%

- – – English learners: 3.4%

- – – Low literacy: 17.6%

- – Racial or ethnic minority: 25.3%

- – Rural: 39.3%

- Population in households lacking fixed broadband availability: 4.2%

- Population in households lacking computer or broadband subscription: 10.6%

- Population not using the internet: 18.5%

- Population not using a PC or tablet computer: 31.9%

While many millions of dollars have been spent trying to map the exact locations of where better Internet is needed, the simplest conclusion, based on existing evidence, is that rural populations (39.3%) and racial or ethnic minorities (25.3%) are the most in need of better Internet. While not everyone in any demographic, ends up voting, the fact that a total of 64.6% of the population is likely to have poor Internet, or be concerned about someone close to them needing better Internet.

Urban vs rural: a false parallel to Democrat versus Republican?

Try zooming in on the US census map here, and compare digital equity in various parts of the state. While voting behavior might be very different in Detroit than in rural counties, notice that problems with broadband Internet access are common to these two supposedly disparate areas.

Glossary

Underserved: An underserved location is defined as a broadband-serviceable location that is (a) not an unserved location, and (b) that the Broadband DATA Maps show as lacking access to Reliable Broadband Service offered with – (i) a speed of not less than 100 Mbps for downloads; and (ii) a speed of not less than 20 Mbps for uploads; and (iii) latency less than or equal to 100 milliseconds (NOFO Section I.C.bb).

Digitally Invisible: How the Internet Is Creating the New Underclass

Nicol Turner Lee

Aug 2024 · Brookings Institution Press

“The previous and future referenda on rural broadband should not come as a surprise from a legislator who understands what it means to live geographically isolated and for a country familiar with and nostalgic for the Rural Electrification Act in 1936 under the New Deal–era President Franklin D. Roosevelt. His efforts allowed the federal government to make low-cost loans to farmers who established nonprofit cooperatives to bring electricity into rural areas.

Decades ago, Senator George Norris (R-NE) expressed concern for farmers or homesteaders from rural America who were not receiving their “fair chance” to participate in the economy due to the economic meltdowns precipitated by the Great Depression. Rural Americans were prematurely growing old and dying, due to the “great gap between their lives and the lives of those whom the accident of birth or choice placed them in these towns or cities.” Through the newly created Rural Electrification Administration by the federal government and the work of rural electric cooperatives, more than 80 percent of farms had electric service by the 1950s, revolutionizing these locations and how they provided their services. Today, rural electric cooperatives continue to exist, providing service to more than 5.5 million rural customers. Over $34 billion has been invested in these types of cooperatives and projects from the U.S. Department of Agriculture since 2009, and the availability of electricity continues to support emerging use cases, including renewable energies and smart grid technologies.

A New York Times opinion writer in 2019 called for the re-creation of a similar entity for rural broadband. Congressman Jim Clyburn (D-SC) and Senator Amy Klobuchar (D-MN) made a similar case with legislation they introduced in 2020. Citing market failures as the primary reason for government intervention, both legislators presented that a more coordinated approach to data collection and deployment would generate better outcomes for the rural poor and business-disadvantaged, whose circumstances have seen little change despite the decades of generous investments.

Rural broadband can be the sweet spot for most legislators, regardless of party line. Notably, in his 2016 presidential campaign, Trump made claims to rural populations as his prime constituents and allies. And the strategy paid off. Rural white men and women flocked to the polls to vote for him over former secretary of state Hillary Clinton due to their heightened anxieties around the economy, jobs, immigration, and the future for their children. Getting broadband to their communities was one of the pillars of the Trump campaign, who vowed to accelerate 5G deployment, restrict Chinese telecom companies from entering U.S. markets, deregulate the industry, and implement infrastructure proposals during his four-year term. Yet by the end of his presidency, Trump was unable to deliver on his infrastructure promises.

During the 2020 presidential election, President Biden included rural broadband development in his campaign. Once in office, he also put forth one of the most aggressive economy recovery plans, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, which I discussed throughout the book so far.”